Port Hope Simpson, view over Alexis Bay

Port Hope Simpson logo, Come Home Year 2002.

The Human Figure represents the spirit of Port Hope Simpson and its enthusiastic fire.

The Labrador Flag represents our heritage.

The House represents the importance of home and family that exists in our community.

The Port Hope Simpson banner represents our town's pride and teamwork. Stacy Russell.

Port Hope Simpson, population 535, is a small town located on the southeastern Labrador coast, 215 kilometres from the Quebec/Labrador border. With the completion of the Trans-Labrador Highway in the region, the area has since had an increase in tourist activity. The town is serviced by Marine Atlantic, and has a ferry connection to a nearby town of William's Harbour. It also has a small regional airport, and is serviced by Air Labrador. It has a friendly, independent people with a compelling history and a priority of sustainable economic development in a region of unspoilt wilderness. Shinneys Water Complex makes up 2,500 square kilometers of over 1000 islands rising dramatically above sea level. These protected waters are ideal for all types of boating and the Alexis River is an excellent salmon river.

Population change

1945: 352 (Source: Southeastern Aurora Development Corporation) 1951: 252 (S.A.D.C.) 1965: 489 (S.A.D.C.) mid 1980s: approximately 650 (S.A.D.C.) 1992: appproximately 530 (S.A.D.C.) 1996: 577 (Source: Statistics Canada) 2001: 509 (S.C.) 2002: 535 (S.A.D.C.)

History of development

The earliest signs of habitation in the Port Hope Simpson area are marks dating from 1773 carved in a rock known as the “stamp from our past” when a few inhabitants were wintering at various places on Alexis and Gilbert Bays. Job Notley and his family were the first permanent inhabitants in the locality living on an island at Light Tickle, to the east of the town’s site and in 1884 a census recorded eight persons living at Alexis River. Development in the area was at a subsistence level based on fishing, trapping and hunting. Any timber cut from dense coniferous woods in the area was limited to building log shacks, trestles, furniture, komatiks and firewood.

It was not until 50 years later that Port Hope Simpson was founded as a logging town in 1934 by John Osborn Williams, owner of the The Labrador development company limited that set-up its pitwood exporting operations on the present site. He was supported in his venture by Sir John Hope Simpson, Commissioner of Natural Resources and Acting-Commissioner of Justice 1934-36. Simpson had agreed to Williams's offer that the settlement should be named after himself. This left The Commission and the British Government wide open to accusations of favouritism in their dealings with Williams.

In fact, as early as 1934, the British Government regretted ever having entered into a business relationship with Williams when they found out that British taxpayers' money had been borrowed under false intentions for development of The Labrador. Williams did not build the anticipated 400 houses for the loggers and their families. Neither did he pay good wages. The people felt betrayed.(1) He kept them in poverty, always in debt by the credit system he used at the Company store. He was only really interested in making as much money as quickly as possible. He was a deceitful, unreliable and untrustworthy businessman. 1934-1940 saw six years of great economic activity as thousands upon thousands of cords of pit props were shipped out from Port Hope Simpson as Britain and her allies prepared for the Second World War.

The reports of Newfoundland Ranger Clarence Dwyer from September 1940 to March 1942 has left us with a snap-shot of life inside the Port Hope Simpson district. The company store was operated ruthlessly, charging very high prices and compelling families to buy from the store under threat of dismissal. Under–nourishment was rife among the coastal communities and many people were desperately poor. People in the north of Dwyer’s district had to share their food to survive. The communities were helping each other but the fishermen continued to be exploited by the merchants who were only paying them very low prices for their salmon and cod. There were still no roads in May 1941 - seven years after the company had first arrived, after promising to support the people and work with them to improve their standard of living. During this time people were leaving for larger earnings elsewhere on construction work at Goose Bay airport and on the island of Newfoundland. Due to the company’s very low wages the remaining loggers went on strike. When they returned to work for the company they were charged increased rents for their housesin proportion to what they earned. Asaph Wentzell, a local man did manage to provide some employment at his sawmill and the general catch of furs continued to be good. By 1942, all the fishing families had left their winter settlement of Port Hope Simpson for their outside summer settlements. Starvation was again facing the people with the high cost of living and the high price of food in Port Hope Simpson. There was also a steady decline in the government’s financial handouts as the people fell back once more on their fishing and trapping to earn a living as the company was closing down. (Source: Newfoundland Rangers’ reports from 30.09.40-09.03.43, Provincial archives, St. John's)

Williams never relinquished legal control of the company to the Government's board of directors in St. John's, Newfoundland and he and his solicitors knew there was nothing the British Government, the Dominions Office nor the Commission of Government could do about it. He had misrepresented his own personal wealth to the government and the wages he paid his loggers had been much less than he had claimed. His actions had a bad effect on the health of people as the loggers were forced to work excessive hours for starvation level wages and deteriorating food from the company's store. Williams was also very economical with the truth about what development was really like on site.

He had borrowed money at a time when the Commission of government was working to cut the Newfoundland debt and when his own country was preparing for war. This was money that he was not in a rush to repay and which he used unscrupulously for other purposes. He even managed to deceive Supreme Court Judge Brian Dunfield at the public enquiry into his Company's financial affairs in 1945 that he necessarily operated on a shoestring implying that allowances should be made accordingly. The government had wanted work and new permanent homes for the people whereas Williams had only wanted to make as much money as quickly as possible and to keep others from the truth of his true financial situation. To hide his high level of earnings from government eyes, the Company's pit props were purchased by one of his other companies - J. O. Williams and Company. Employees in Port Hope Simpson could never tell whether or not they were getting the full value for their products in their wage packets.

Whilst this was all going on, Williams was himself being cheated by Keith Yonge, his manager in Port Hope Simpson about the sale of goods from the store. Williams sent Eric, his eldest son out, to report back about what was really happening.

He never returned. He died in acrimonious circumstances in what was reported at the time as a house fire with Erica, his infant daughter. (The Evening Telegram, 3 February 1940, St. John's, Newfoundland)

At this point a cover-up about the deaths was put in place beginning with the appointment of Claude Fraser, Simpson's loyal secretary of Natural Resources, as Government Director of the company on exactly the same day as the deaths occurred. The Commission was concerned that they should not be found guilty of mismanaging the company over which they were supposed to have control at the time. They did not want to be liable for any claim for compensation that Williams might make against them. Williams was able to successfully hold the threat of a claim as a powerful bargaining chip against the British government which meant he later left the Labrador with a lucrative financial pay-off. For their part, the British government was pleased to see an end to what they had described as a sordid affair.

Fraser's death was followed-up not long afterwards by the appointment of Thomas Lodge to the same post. Lodge was the former Commissioner of Public Utilities 1934-37 who had been disgraced in the eyes of the Dominions Office in London for the publication of his book Dictatorship in Newfoundland about the inner workings of The Commission that ruled Newfoundland and Labrador at the time.

Further evidence for a cover-up is also found by, for example, discrepancies in the inscription chosen by Williams on the tombstone in Port Hope Simpson to the deceased; surviving relatives of Eric and Olga on both sides of the Atlantic view the deaths as something that is not talked about; a missing police report about the deaths even though there was a Newfoundland Ranger based in the settlement at the time; a missing medical report even though a Doctor was in attendance at the scene; many Newfoundland Ranger reports missing from Labrador and Sir John Hope Simpson having been consistent over the years in battling to keep the Newfoundland Rangers under the authority of his old Department of Natural Resources instead of agreeing to them being relocated under the more rational jurisdiction of the Department of Justice.

In August 2002 The Royal Canadian Mounted Police, under the Department of Justice, decided to open up their own investigation about whether or not foul play had occurred. Since no satisfactory explanation for what happened has yet been found their file remains open.

Williams family memorial inscription, 29 July, 2002

Arthur Eric Williams, 21 years, (30.07.13-03.02.1940); Erica D'Anitoff Williams, (15.07.36-03.02.40) photograph unavailable; Port Hope Simpson, August 1934

A crucible of political, economic and social factors has been influential in the development of the town. Different characters, government officials and policies, the availability of work and how well its people have adapted to changing economic circumstances have combined together to explain the nature of its growth. When the Company left in 1948 leaving confusion, bitterness and a hoary, wild west reputation in its wake, paid work in the woods left with it until Bowaters arrived 14 years later.

Further economic development took place from 1962-1968 as Bowaters picked-up the thread of economic development laid down by Williams, Simpson and the Labrador Development Company. More trees were felled, this time for their pulp and paper mills at Corner Brook, Newfoundland and in Kent, England. They left good benefits of regular paid employment for the community, 20 miles of forest roads and the government contributed by sharing the cost of building a new wharf. Whilst Williams and his company had left behind a bad legacy of mysterious deaths and unsustainable development.

In 1970, apart from the post office, the general store and the two schools there was no year-round paid employment available. Without paid work from Bowaters, the people were forced to rely upon unemployment benefits for the long winter and their traditional hunting, fishing and boat-building skills to see them through. Only a limited amount of trapping went on. Work was limited to cutting firewood and timber for house-building.

From 1970 to 1992 cod and salmon fishing was the economic mainstay of the area but since this was limited to the short summer months, unemployment prevailed most of the year round with the men folk occupying themselves as best they could. In 1992 the cod fishery was closed down altogether because the cod had disappeared and the government had imposed a cod moratorium. However, many local fishermen had cleverly prepared themselves in anticipation of what they had already forseen. They made the transition into crab, shrimp and scallop fishing relatively easily. Nevertheless, the 1990s was a very difficult time for the people with the loss of their traditional fishery and source of income. They responded by buidling hand-crafted trawlers that took to the seas many of them from Mary's Harbour on the outside.

In 1996, Port Hope Simpson was granted the status of a Canadian town under the municipalities act of the Government of Newfoundland.

Manufacturing industry had been developed by men like Simon Strugnall who had now diversified into logging from boat-building. Two large–scale injections of federal and provincial money meant that long-term government developments for Port Hope Simpson and its area were underway. The huge construction works of The Trans-Labrador Highway; the new Port Hope Simpson bridge and the airport on the outskirts of town (part of an overall government programme for other communities along the coast) with scheduled passenger and freight service to St Anthony and Happy Valley-Goose Bay have done much to increse accessibility. Improved accessibilty has been a crucial factor in bringing visitors to the town as the people have been able to develop Port Hope Simpson into a much better place in which to live.

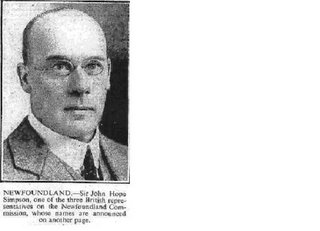

Sir John Hope Simpson, (23 July 1868 - 10 April 1961) 66 years- the younger looking photograph of the new Commissioner placed in The Times, London p.16, 22.01.1934

Sir John Hope Simpson 66 years Port Hope Simpson naming ceremony

John Osborn Williams, (28.03.1886-06.07.1963) owner, Labrador development company limited, Port Hope Simpson

Olga Marie Wiseman (Williams) nee D'Anitoff b.1915 d. 08.11.04

Keith Yonge/Young/Younge, manager, Labrador development company limited, Port Hope Simpson

Keith Yonge/Young/Younge, manager, Labrador development company limited, Port Hope SimpsonCitation

1: R.C.M.P. investigation report, Serious Crimes Unit, Gander, Newfoundland 2004

Sources

http://www.statcan.ca Canadian Statistics

http://www.ourlabrador.ca Our Labrador...Yours to Explore, Smart Labrador and Combined Councils of Labrador 1995;

http://porthopesimpsonsdevelopment.blogspot.com Port Hope Simpson history of development with photographs Llewelyn Pritchard 2004;

http://twounsolveddeaths.blogspot.com Port Hope Simpson two unsolved deaths, Llewelyn Pritchard 2004;

http://www.southeastern-labrador.nf.ca Southeastern Aurora Development Corporation 2002;

http://mysite.wanadoo-members.co.uk/porthopesimpsonhist Tombstone - a history of development, including list of sources on which this article is based, Llewelyn Pritchard 2002;

<< Home